A fully digitized record of the Nuremberg trials is now online, opening one of the most consequential legal archives of the 20th century to anyone with an internet connection.

The launch coincides with the 80th anniversary of the trials’ beginning, a moment that reshaped international law and forced the world to confront the machinery of Nazi crimes. What began as a cautious preservation effort in the late 1990s has become a comprehensive public resource: every official document held by Harvard Law School’s library, all 750,000 pages of transcripts, exhibits, briefs, and supporting material, made accessible after a painstaking 25-year project.

The work started almost humbly. In 1998, archivists began removing staples and paperclips from fragile mimeographed pages that were literally crumbling at the touch.

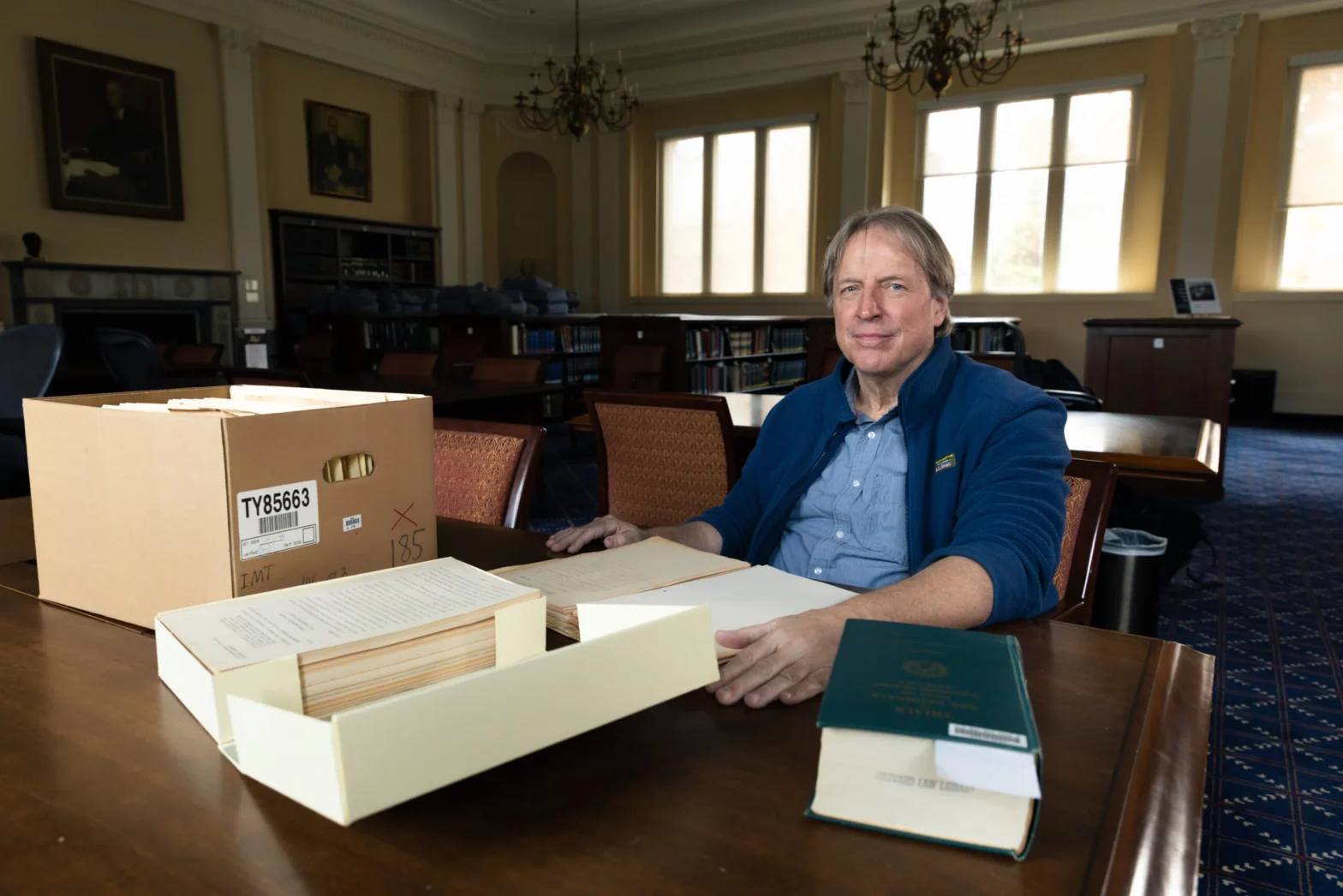

The documents, printed on 1940s acid-based paper, were degrading so quickly that preservation could not be delayed. Under the direction of Paul Deschner, the project’s guiding force, the team committed to scanning and cataloguing every piece of material tied to the trials. Until then, much of it sat dormant in boxes, consulted rarely and handled even less. The goal was twofold: protect a fading historical record and bring it into the emerging digital era, where access would no longer depend on an in-person visit to the library’s basement.

The Nuremberg archive is daunting both in scale and in weight.

It includes transcripts that capture the rhythm of the courtroom from start to finish, along with the documents prosecutors and defense lawyers relied on. Across 13 trials held between 1945 and 1949, almost two hundred Nazi military and political leaders were prosecuted for crimes against humanity, above all the Holocaust. The first and most famous trial put 19 senior figures, among them Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, and Albert Speer, before an international court. Only three defendants across all proceedings were acquitted. Twelve were sentenced to death; others received life imprisonment or shorter terms. These outcomes helped redefine what accountability meant in the aftermath of state-sponsored atrocity.

The digitised collection does not soften the brutality contained within it. Some documents speak bluntly, others hide violence in cold bureaucratic language, but together they reveal the step-by-step construction of genocide. Deschner notes that the archive shows how ordinary administrative acts in the early 1930s grew into the machinery of mass murder. He hopes users will approach the material with an awareness that it still has something to teach: patterns of authoritarian thinking, early signs of radicalisation, and the ease with which institutions can normalize the grotesque.

Requests for access have already come from all corners. Historians, filmmakers, students, and family members of those connected to the trials have begun exploring the collection. Some search for legal history, others for traces of relatives who testified or served on legal teams. The project arrives at a time when universities and researchers face growing pressure, particularly in the United States, where debates over academic freedom and the role of higher education have sharpened. Against that backdrop, Deschner sees the archive as a quiet but meaningful assertion of fact. When disinformation spreads easily and bad-faith arguments flourish, the importance of direct, verifiable documentation becomes harder to overstate.

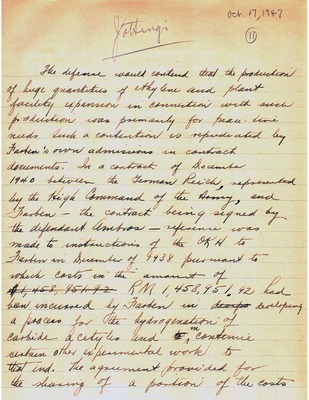

He points out that each exhibit rests on a long paper trail: original government documents, photostats, translations, typed copies, and summaries. This layered process strengthens the evidentiary chain, something indispensable in an era when Holocaust denial still circulates. In his view, offering unfiltered access to these materials is one of the surest ways to counter those who insist that the truth can be doubted indefinitely.

Even the mechanics of the trials hold untapped interest. The courtroom relied on simultaneous translation, then a novel technique, as English, German, French, and Russian were spoken in rapid succession. Stenographers transcribed the translators’ words; typists produced final versions. Each step introduced its own interpretive layer, and Deschner believes the linguistic dimension of the trials remains understudied, rich with questions about how law functions across languages under extraordinary pressure.

Amanda Watson of Harvard Law School emphasizes that preserving these records is only half the task; sharing them is the rest. She sees the release as an answer to a broader question the trials themselves posed: how law can respond to moments of global crisis. Making these materials visible, she argues, ensures they remain part of public understanding rather than fading into inaccessible archives. The project’s completion does not feel like a closing of history but a reopening, an invitation for a new generation to examine, question, and learn from a record that was once locked away.

The digital release also arrives at a moment when the international legal order faces renewed challenges. Scholars have increasingly noted parallels between the fragmentation of the current global system and the uncertainty that surrounded the world in 1945. The Nuremberg record captures the early struggle to establish norms governing genocide, aggressive war, and crimes against individuals regardless of rank. These principles later shaped the Geneva Conventions and the founding charter of the International Criminal Court. By making the archive accessible, researchers can now study, in granular detail, how these legal concepts were argued into existence, challenged, and eventually codified. It offers not just a historical record, but a blueprint showing how international law was stitched together from contested ideas.

Another value of the archive lies in its depiction of institutional complicity. Modern human rights investigators examining atrocities in places like Syria, Myanmar, or Ethiopia often grapple with proving chains of command, bureaucratic intent, and administrative coordination. Nuremberg’s meticulous documentation provides a comparative foundation. The files show how orders flowed, how euphemisms masked violence, and how technical departments, transportation, medical bureaus, procurement offices, played indispensable roles in genocide. Contemporary war crimes prosecutors have already drawn on Nuremberg in shaping indictments at tribunals in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia; this digitised trove will deepen that lineage, giving legal teams access to historical parallels that can strengthen modern cases.

There is also a cultural dimension that the archive now makes easier to explore. The Nuremberg transcripts reveal a courtroom wrestling not only with facts but with language, memory, and the psychological weight of mass atrocity. They show moments of hesitation, flashes of disbelief, and the difficulty of articulating crimes that had no precedent. Literary scholars and ethicists have long argued that Nuremberg helped expand the vocabulary of global morality, words like “genocide,” “crimes against humanity,” and “the responsibility of leaders” entered public consciousness through these proceedings. In an era defined by fragmented narratives and competing claims to truth, the availability of these original records offers a rare opportunity: the chance to watch, almost in real time, as the world struggled to describe the indescribable and to create a moral framework sturdy enough to confront it.

These additional layers of context, legal, political, and cultural, point to why this archive matters now as much as it did eight decades ago. The digital release is more than a preservation effort. It is a reminder that the fight to define truth and to defend it never ends.

To access the full collection, see Harvard’s archive online, here: https://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/