China and Japan have argued over Taiwan before, but this time the disagreement has traveled farther and hardened faster than most diplomats expected. What began as a brief parliamentary remark in Tokyo has now surfaced at the United Nations, transformed into a proxy battle over history, sovereignty, and the shifting balance of power in East Asia. The language is sharper than usual. The patience on both sides thinner. And the stakes, though still unfolding in rhetoric rather than action, are uncomfortably clear.

The spark was simple enough. During a routine Diet exchange, Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi acknowledged that a Chinese assault on Taiwan, barely a hundred kilometers from Japanese territory, could legally be deemed “a situation threatening Japan’s survival.” Under Japan’s security legislation, that classification allows the prime minister to deploy the Self-Defense Forces. It was a sterile, hypothetical answer delivered in the dry vocabulary of legal thresholds. But for Beijing, it crossed a line.

China’s reaction landed as a pointed letter at the UN. Ambassador Fu Cong accused Japan of a “grave violation of international law,” warning that any attempt by Tokyo to “intervene militarily” in the Taiwan Strait would be treated as aggression. He vowed China would “resolutely exercise its right to self-defense.” It was the strongest formulation Beijing has aimed at Japan in years.

Tokyo rejected the accusation within hours. Officials insisted the government’s position had not changed whatsoever, describing Beijing’s claims as “entirely baseless.” Still, China has treated Takaichi’s statement as escalation. What Tokyo sees as constitutional hygiene, Beijing interprets as a strategic reveal.

The dispute has not stayed inside the usual diplomatic lines. In the past two weeks, tensions have seeped into culture and commerce: Japanese concerts in China canceled without explanation, Chinese tourists scrapping trips to Japan, social media campaigns portraying Japan as flirting with “renewed militarism.” At one point, the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo posted that China could take “direct military action” without UN approval because Japan still qualifies as an “enemy state” under World War II era UN Charter clauses. The post was as theatrical as it was unsettling.

History is doing new work here. Beijing has increasingly invoked the Cairo and Potsdam declarations, the wartime statements envisioning the return of territories seized by Imperial Japan. Mainland China treats them as binding legal documents that affirm sovereignty over Taiwan. Many countries do not. And the historical wrinkle is larger than it first appears: the government that signed those declarations, the Republic of China, is the government that now rules Taiwan from Taipei, not Beijing. For Chinese officials, however, the lineage matters less than the symbolism.

Meanwhile, Japan is trying to explain what it meant without apologizing for what it said.

Takaichi has acknowledged she will avoid specifying hypothetical troop deployment scenarios in the future. But she has not walked back her remarks, nor does she seem inclined to. The government maintains it has long treated Taiwan’s security as inseparable from Japan’s own. The difference is that it once avoided stating this explicitly. That ambiguity, once a shared diplomatic cushion, is now collapsing under the weight of public statements and political suspicion.

The timing has only magnified the tension. This year marks the 80th anniversary of Japan’s World War II defeat, a milestone China is already using to frame Japan as drifting away from its postwar commitments. Tokyo, for its part, has been accelerating joint exercises with the United States and Australia, modernizing its defenses, and talking more openly about the realistic consequences of a Taiwan conflict. In Beijing’s eyes, this forms a pattern. In Tokyo’s view, it is overdue preparation.

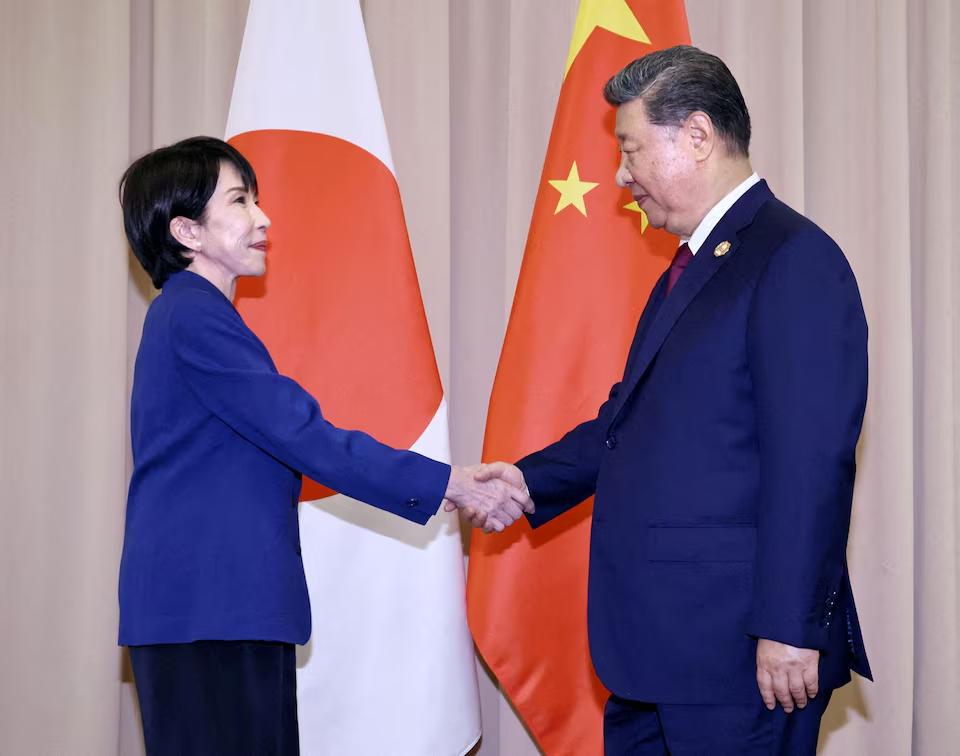

There is very little personal diplomacy softening the moment. At the G20 summit in Johannesburg, Takaichi and Chinese Premier Li Qiang shared a stage but not a conversation. They stood only a few people apart during the group photo. Still, no meeting was requested, and none occurred. Chinese state media chose to highlight that Takaichi arrived nearly an hour late to the proceedings. It was a minor detail that was inflated into a diplomatic slight.

Both governments have reasons to manage this calmer than their words suggest. China is Japan’s largest trading partner and a critical supplier of rare earth minerals. Japan remains one of China’s biggest markets for tourism and cultural exchange. Yet trade and sentiment can shift quickly when a political quarrel hardens into a narrative of national insult. The early signs, including canceled performances, travel hesitations, and tightened inspections on Japanese seafood, hint at the sort of informal pressure Beijing often uses when formal channels stall.

China sees any external comment on Taiwan as interference in its internal affairs. Japan sees any conflict around Taiwan as inherently intertwined with its own security. These views are not symmetrical, and they do not meet in the middle. Instead, they clash in the gray space where law, geography, and memory overlap. Every statement, even one framed as hypothetical, becomes a new starting point for mistrust.

Where this leads is difficult to predict. Neither side wants a military confrontation, yet both have adopted language that describes one as more plausible than before. China is warning about “self-defense” under the UN Charter. Japan is openly discussing survival-threatening scenarios.

Moments like this can burn themselves out through diplomatic fatigue, or they can settle into a new normal that feels stable until the next provocation tips it over.

The uncomfortable truth is that each round of escalation becomes part of the reference record, quoted back later as justification for stronger language or firmer policies. Over time, that cumulative weight can shift expectations.

For now, both governments appear to be signaling resolve rather than seeking a path back to steadier ground. Yet regional stability usually hinges not on the sharpest remarks but on the quiet work that follows them. If there is an off-ramp, it will not come from a single letter at the UN or a clipped rebuttal at a summit photo line. It will come from each side remembering that, in Asia’s crowded strategic landscape, ambiguity is often not a flaw but a buffer, one that is far easier to discard than to rebuild.