Japan’s latest clash with China did not unfold in a press conference or a televised speech, but in the quiet, formal language of letters filed at the United Nations.

Beijing went first. Tokyo answered. And between those two documents you can see just how far the argument over Taiwan, history, and regional power has spread.

China’s permanent representative to the UN, Fu Cong, sent a letter to Secretary-General António Guterres on Friday, accusing Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi of making “gravely erroneous” and “extremely dangerous” remarks when she answered a question in the Diet earlier this month about a Taiwan contingency. In that exchange, Takaichi said that a Chinese attempt to bring Taiwan under its control through battleships and military force could amount to “a situation threatening Japan’s survival,” the specific legal phrase that allows a Japanese prime minister to invoke collective self-defense and deploy the Self-Defense Forces alongside allies.

For Beijing, that crossed several lines at once. Fu’s letter argued that this was the first time since Japan’s defeat in 1945 that a Japanese leader had, in an official setting, explicitly linked “a contingency for Taiwan” to a contingency for Japan and tied it to collective self-defense. He framed it as Japan openly expressing ambitions to “intervene militarily in the Taiwan question” and issuing a threat of force against China. He went further, saying such remarks violated international law and post-war norms, undermined the international order, and insulted not only the Chinese people but other Asian nations that suffered under Japanese occupation. If Japan ever “dared” to intervene armed in the Taiwan Strait, Fu warned, China would treat it as an act of aggression and “resolutely exercise its right of self-defence” under the UN Charter.

Tokyo’s response, delivered on Monday by Japan’s UN ambassador Kazuyuki Yamazaki and also addressed to Guterres, was deliberately restrained in tone but sharply worded in substance.

The assertions in China’s letter, he wrote, were “inconsistent with the facts and unsubstantiated,” and it was precisely because of that that Japan felt compelled to put its own position on record.

Yamazaki’s letter reads like a guided tour through Japan’s post-war defense identity. Since 1945, he noted, Japan has tried to demonstrate in practice that it is a contributor to peace, operating under a constitution that heavily constrains the use of force. He restated what Tokyo calls its “passive defense strategy”, an exclusively defense-oriented posture that rejects pre-emptive attack and tightly limits the circumstances in which Japan might use armed force, even in support of allies. Japan’s right to collective self-defense may be recognized under the UN Charter, he said, but domestic law restricts how and when that right can be exercised.

From that standpoint, Takaichi’s comments, he argued, do not indicate a new militaristic ambition, but simply apply the existing legal framework to a hypothetical scenario that any serious security planner now has to consider: a major war over Taiwan spilling into the waters and airspace around Japan’s southwest islands.

In that sense, the prime minister said out loud what security legislation passed in 2015 was always designed to address. To claim that Japan is preparing to exercise self-defense “even in the absence of an armed attack,” Yamazaki wrote, is “erroneous.”

He then turned the argument back on Beijing.

Without naming China, the letter pointed to “certain countries” that have been expanding their military capabilities in opaque ways and trying to change the status quo by force or coercion, despite opposition from neighbors. Japan, he said, opposes such moves and “distances itself from them.” It was a thinly veiled reference to China’s military build-up, its pressure on Taiwan, and its activities around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, which Japan administers and China also claims.

On Taiwan itself, Yamazaki went out of his way to say that Japan’s basic position has not changed since the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué: Tokyo recognizes Beijing as the sole legal government of China, “fully understands and respects” China’s position that Taiwan is part of China, and maintains only unofficial ties with Taipei. At the same time, he stressed that peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait are “extremely important” for Japan and for the international community, and that Tokyo expects issues concerning Taiwan to be resolved peacefully through dialogue.

The letters would matter less if they were isolated. They are not. They sit on top of a month-long spiral that began with Takaichi’s November 7 remarks and has since pulled in trade, travel, culture, and public opinion. A Reuters timeline of the crisis reads almost like a checklist of modern pressure tools: warnings to Chinese citizens about visiting Japan, new restrictions on Japanese seafood imports just months after a partial lifting of earlier bans, suspended talks on resuming Japanese beef exports, airlines offering fee-free changes for China-Japan routes, and even cancellations of Japanese film screenings. Cultural diplomacy has turned into cultural punishment.

Online, Chinese diplomats have dusted off their “wolf warrior” playbook. The Chinese consul general in Osaka posted, and then deleted, a remark on X suggesting that the “dirty head that sticks itself in must be cut off” after Takaichi’s Taiwan comments, language widely read in Japan as a violent metaphor aimed at its prime minister. Other embassies in Asia reposted wartime imagery and caricatures portraying Japan as sliding back into militarism, complete with ghosts of the past hovering over Takaichi. Beijing’s messaging has leaned heavily on memories of Japanese wartime atrocities, particularly in territories it once occupied, to frame today’s debate about Taiwan as a test of whether Japan can be trusted to remain on a “peaceful development” path.

Japan’s government has tried to walk a narrow line in response. It summoned the Chinese ambassador to protest the Osaka consul’s post and described the comments as “extremely inappropriate,” while Takaichi herself called her own remarks “hypothetical” and promised to avoid similar language in the Diet going forward. At the same time, Tokyo has refused to retract the substance of what she said. Officials repeat that the legal concept of a “survival-threatening situation” exists precisely because a crisis in nearby waters, even if it begins elsewhere, could quickly endanger Japan. For a country that depends on sea lanes and is within easy missile range of China, that is not an abstraction.

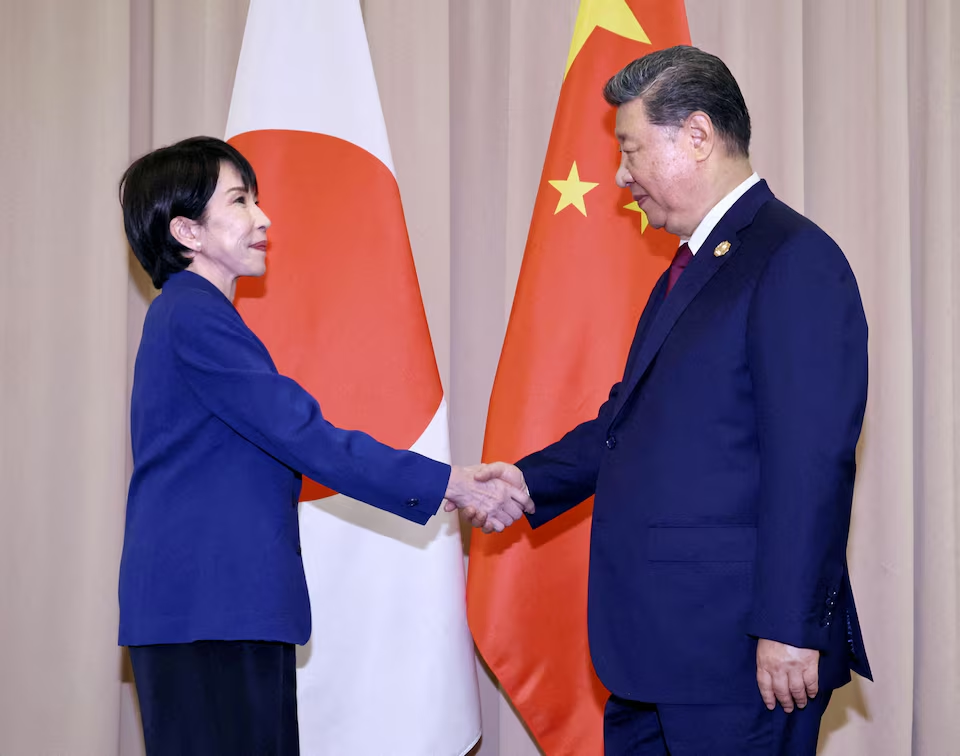

The United States is unavoidably in the background of all this. Japan’s security laws were revised to allow limited collective self-defense primarily so it could operate more seamlessly with U.S. forces in a contingency. Washington, for its part, has been deepening security ties with Japan and other regional partners, and American officials have long warned that conflict over Taiwan would drag in U.S. allies. As the rhetoric climbed, former President Donald Trump told reporters he had a “great talk” with Takaichi and emphasized open communication after her recent conversation with China’s Xi Jinping, but he has not publicly taken sides in the letter war itself. Even that studied ambiguity is part of the story: everyone knows the alliance is central, even when it is not explicitly named.

What makes the UN exchange noteworthy is that both sides chose to internationalize the dispute in a very formal way. China’s letter was a warning shot meant for a global audience, positioning Takaichi’s remarks as a violation of international law and a threat to the post-war settlement that governs East Asia. Japan’s reply, in turn, was aimed at countering that framing before it hardens into conventional wisdom in capitals that may not follow the intricacies of Japanese security law. Each wants its narrative sitting in the UN’s official record for the next time tensions flare.

Underneath the legal language and diplomatic politeness lies a simpler reality. China wants to deter any hint that Japan might get involved militarily if Taiwan is attacked. Japan wants to deter China from assuming it can fight a war over Taiwan without triggering a wider regional response. Both are signaling to the other, and to everyone watching, how they interpret the boundaries of risk.

The letters do not resolve any of that. But they do show that the argument has moved from press podiums and social media into the formal architecture of the UN. That alone is a reminder of how narrow the margin for miscalculation has become. In a region where history is never truly past and geography cannot be negotiated, a carefully worded paragraph in New York can feel like the opening move in the next round of a very old contest.