International Criminal Court prosecutors made clear on Friday that the arrest warrants issued for Vladimir Putin and five other Russian officials will not simply disappear, even if U.S.-led peace talks end with a sweeping amnesty for actions committed during the war in Ukraine.

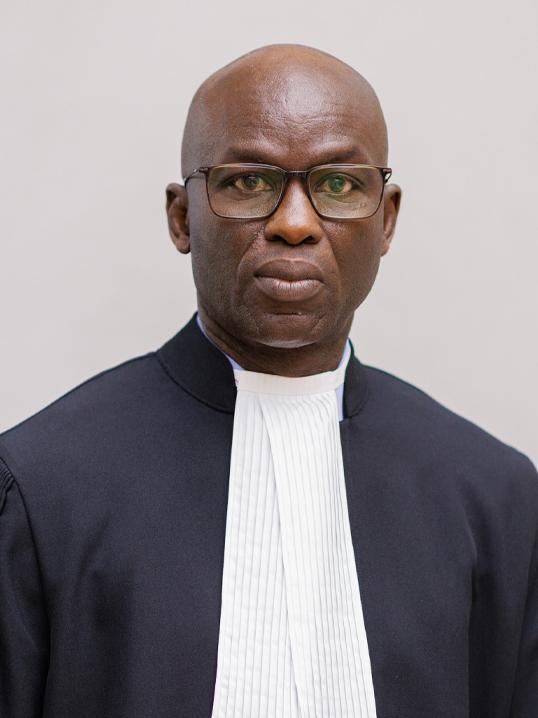

Speaking in The Hague, Deputy Prosecutors Mame Mandiaye Niang of Senegal and Nazhat Shameem Khan of Fiji underscored that only a United Nations Security Council resolution could pause or defer the warrants, and even that would not amount to erasure. Their message was blunt: political deals may shift, but the court’s mandate under the Rome Statute remains fixed.

The warrants, first issued for alleged atrocities committed after Russia’s 2022 invasion, accuse Putin and several senior figures of overseeing grave violations, including the illegal transfer of hundreds of Ukrainian children. The Kremlin has rejected both the allegations and the court’s authority, a stance consistent with its long-standing refusal to recognize the ICC.

Other high-ranking Russians remain wanted as well, among them former defense minister Sergei Shoigu and General Valery Gerasimov, both accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity for attacks on civilians.

Khan told Reuters that peace negotiations, no matter how ambitious or politically sensitive, do not override the obligations written into the court’s founding statute. If the Security Council were to request a deferral, she said, that would be its own political process, but it would not alter the ICC’s definition of justice or the cases already under way. Niang echoed the point, noting that the court cannot bend its work around diplomatic compromises, except in the narrow circumstances allowed under international law.

Their comments come after an early version of a 28-point U.S. draft peace proposal surfaced in November and set off alarms in Kyiv and across Europe. The draft suggested granting “full amnesty” to all parties involved in the conflict, a concession that many saw as indulging Moscow’s primary demands. For Ukraine, that idea is impossible to swallow.

Andriy Kostin, its ambassador to the Netherlands and a former prosecutor general, said the scale of atrocities committed over the last several years rules out any sweeping immunity. Crimes of that magnitude, he argued, cannot be brushed aside for the sake of expediency.

The atrocities at the heart of the ICC’s case are not theoretical. Investigators have documented forced transfers of Ukrainian children from occupied territories into Russia, often under the guise of “evacuation” or “protection.” Many were relocated thousands of miles away, placed in camps or foster arrangements without parental consent, and subjected to efforts to erase their identity. Kyiv has traced only a fraction of these children, a process slowed by bureaucratic obstruction and the sheer geographic sprawl of transfers. It is one of the reasons the idea of a blanket amnesty strikes Ukrainian officials as not just politically unacceptable but morally incoherent.

Also included are cases tied to deliberate attacks on civilian areas across the country. Prosecutors point to patterns rather than isolated events: bombardments of residential districts far from active fighting, the targeting of energy infrastructure during winter months, and strikes on evacuation corridors that had previously been negotiated. Human rights monitors have logged hundreds of incidents where civilian casualties were not a byproduct of imprecision but the foreseeable outcome of decisions taken by senior command. These are the types of acts that form the backbone of war crimes and crimes-against-humanity charges against Russian officials like Sergei Shoigu and Valery Gerasimov. For the court, these events define the limits of what can be traded away at a negotiating table. And for those who lived through them, they shape the kind of peace that would be credible enough to endure.

The ICC stands as the world’s permanent tribunal for prosecuting war crimes, but its authority has limits shaped by geopolitics. Russia, China and the United States are not members of the court and have openly challenged or rejected its jurisdiction. Even so, the prosecutors’ message conveyed a certain steadiness: whatever emerges from negotiations, the legal clock set in motion by the court continues to run.

The ICC’s refusal to void Putin’s arrest warrant, even if a U.S.-led peace deal includes amnesty, lands unevenly across major powers: Washington faces the awkward tension of promoting diplomacy while appearing to sidestep a court it selectively supports; Tokyo sees the ICC’s firmness as reinforcing its own argument that international law must anchor responses to aggression, especially amid rising regional tensions; and Europe, aligned with Kyiv, worries that any blanket amnesty would set a dangerous precedent by allowing major powers to negotiate away accountability.